The Derwent Mill is situated in Cockermouth on the banks of the river Derwent, a powerful river which

begins in Borrowdale and flows into the sea at Workington. The market town of Cockermouth lies at the

confluence of the rivers Cocker and Derwent and is famous, not only for the birth of William Wordsworth

but was represented in parliament by some of the most foremost men of their day. Cockermouth

was the first stopping place on the road to London when Maryport was one of the countries largest ports

handling much of the American trade.

Alongside the Derwent and Cocker rivers, two smaller streams also run through the town - the Tom Rudd and Bitter Becks. ‘ It was the water power provided by the rivers and these two streams which in the industrial revolution greatly changed the life of Cockermouth, adding a considerable number of mills and factories to an already important market town. In 1829 there were over 40 industrial sites - including 5 corn millers, 4 woollen firms, 5 cotton manufacturers, 7 tanners and 5 flax and linen manufacturers.’ Cockermouth 150 years ago was a largely self sufficient market town.

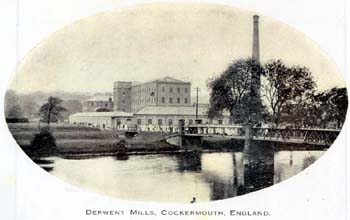

Foremost amongst the industries mentioned is the Flax Mill of Messrs Jonathan Harris and Sons, a now foreboding building which stands largely in ruins by the edge of the river Derwent. It is this mill and their prosperity from the mid 19th century to their final closure in 1934 on which I have based my project.

The history of the Harris Thread business began around about 1800 when two cousins began a weaving shop in Eaglesfield: they were Jonathan (1783-1869) and William (1782-1829). It was a successful venture enabling them to take a big step and purchase the Low Gote Mill in Cockermouth around 1808.

Up until that date the mill had been used as a corn mill.

The family were descended from Isaac and Hannah Harris, Isaac

being a Friends minister for 50 years and described as devout

and honest with no respect for show.

Before the growing of cotton became general in the United States,

flax was the world’s most important raw material for the

manufacture of textiles.

The use of flax fibre for cloth originated almost 10,000 years

ago. At one time large quantities were produced in Great Britain

- the nearest flax mill to Cockermouth being at Cleator in West

Cumbria.

Whether or not this is where the Harris family first got their

flax I have found no information, but there is a reference to

the mountain of home grown flax in ‘The royal Album of Arts

and Industries’. Flax was grown in Ireland on a limited scale

which could be shipped to Maryport then taken by road to Cockermouth.

Their is also mention of flax being grown at Blennerhasset which

is about 5miles from Cockermouth. Appendix (1)

With the majority of textile mills located in Lancashire the flax

could have been brought by road from there though railway networks

to Cockermouth

were being developed by the 1840s. Appendix (2)

Flax is a delicate plant about two feet high with long narrow

leaves and pale blue flowers. The best soil for growing flax is

a heavy, rich, well-drained loam. The fibres vary in length from

three quarters of an inch to one and a half inches. They overlap

each other and are held together by a gummy matter to build up

the larger or commercial fibres. After lifting, the plants are

subjected to a coarse combing to remove the seed pods. They are

then retted (the straw being spread on the ground in order to

subject it to the action of rain,dew and micro-organisms) to separate

the fibres from the woody parts of the stems. After drying they

are ready for cleaning and prepared for spinning. The fibre products

include linen threads, fine linen fabrics, twine, towelling, canvas

and lace. The seed is the source of linseed oil and cattle meal.

Appendix (3).

In 1820 a building known as the ‘Hospice’ was erected for drying the flax and in 1834 the Derwent Mill was built to accommodate the expanding linen business. Water was supplied to the mill from the Gote Mill Race, the course of which can still be traced today. Appendix (4).

The business flourished, although textile industries in the

North of Cumbria were declining from the 1840s onwards with work

being found further afield in the growing Lancashire textile towns.

Jonathan’s son Joseph had now entered the business and from

small beginnings the works grew into a large undertaking, capable

of employing between 800 and 1,000 operatives, mainly women and

girls. During the Chartist riots of the 1840s when police protection

was offered by the local authorities against possible violence,

it was respectfully declined by Jonathan Harris with the remark

“ I will trust my work people to protect my property and

their own source of livelihood”.

His confidence was justified and ‘No disturbance of amicable

relationship, nor

such misfortune as a strike has ever intervened’. (1)

The Harris family were reputed to have their own fire service

and during the 1880s started up a free school for their work people

aged between 16 and40 years.

One of the main reasons for the success of the Harris family during the 19th century was due to their investment and commitment to new ideas. Steam engines were installed into the mill in 1835 and1849.

During the 1850s the Harris family supplemented their original

business of flax - yarn spinning and weaving by the manufacture

of sewing threads.

With the use of the latest machinery they developed this particular

line of the flax spinning industry and obtained a world wide reputation

for the quality of their goods. Special attention was given to

the capabilities of the fibre of flax as a substitute for silk

and other foreign fibres. A process was perfected at great cost

which showed conclusively that of all known fibres, flax, though

difficult to manipulate was the one best capable of giving “truly

aesthetic effects”.

The solicitors documents in Whitehaven archives listed a licence

taken out in 1852 to use an invention which improved the manufacture

of thread and yarn.

The Harris family also discovered during the course of their

experiments that the flax fibre was capable of permanently retaining

almost all the shades of brilliant colours which can be used on

other fibres eg silk, wool, cotton etc.

The flax took on all the lustre and tone necessary for use in

all high class embroidery and at one third of the price of good

filoselle silk. By the 1980s the Derwent mills had devoted their

attention to the production of Pure Flax Embroidery threads gaining

a high reputation for use on the finest fancy goods and fabrics,

to the solid and substantial work required in decorative upholstery.

The threads were used by various schools of art needlework, ladies

guilds, work societies and also machined embroideries.

Their threads are well described in a quote taken from The Australian

Trading World. Appendix (5).

“From an aesthetic point of view, the Flax Embroidery Thread is decidedly superior to silk as it carries with it that peculiarly subdued yet characteristic tone that is so much approved in modern art. It is hardly necessary to refer to the great tensile strength of the thread, a quality that will be appreciated by all embroiderers. If the article is subjected to any amount of ordinary wear the flax is by far superior to the silken fabric.”

Harris threads were exported to Sydney, Melbourne and Calcutta. Offices and showrooms of the firm were at 53, New Bond Street, moving to 25 Old Bond Street by 1890. Specimens of work in the showrooms included heraldry, ecclesiastical work, crests, monograms, household decorations, table and bed linen, ladies fancy work etc. Appendix (6).

“This collection may aptly be called the pioneer exhibition of what is destined to become a new industry, with a great future before it, and in which a home-grown product will play a part which has hitherto been the exclusive prerogative of silk or other fibre of foreign origin.”(2)

There is a mention in this article from “The Royal Album of Arts and Industries of Great Britain. ” of Harris and Sons succeeding in their object of encouraging the demand for a native fibre, for which the climate and soil of the three kingdoms being particularly well suited.

Joseph Harris died in 1883 and on the 10th of August 1895, Harris Park in Cockermouth was officially opened by Mrs Joseph Harris in memory of her late husband. Appendix (7).

The business was taken on by Jonathan James Harris, nephew

of the late Joseph. I have notes on a T. M. Harris (son of Joseph)

but cannot find what part he played in the running of the firm.

Jonathan James Harris was born on June 22nd 1841 and educated

at a ‘Friends’ private school at Alderley in Cheshire.

Upon the death of his uncle he gave up a personal preference for

the medical profession to take over the business. In 1893 he married

a daughter of the late Mr James Porter Henderson of Liverpool

and Belfast. Also in that year the firm was converted into a private

limited company, Jonathan Harris becoming chairman and managing

director.

From the solicitor’s files there is a copy of an agreement

to Messrs. Harris & Sons to sell their shares to one Jonathan

James Harris.

This states that: 1. The Number of members of the Company (exclusive

of persons who are in employment of the Company is limited to

fifty. 2. No invitation to the public to subscribe in any shares

or debentures shall be made. 3. Borrowing should not exceed £3,000.

Jonathan James Harris remained head of the family firm for many

years.

The firm prospered with wholesale showrooms opening in Birmingham,

Glasgow, Liverpool, Manchester and Paris. Appendix (8).

‘A stall of Harris Art Linens embroidered in thin flax threads

won a gold medal in Manchester and Derwent shot dress linens were

included in the trousseau of Princess of Wales.’

Visitors to Cockermouth were invited to inspect the showrooms

of Jonathan Harris and Sons. Tours of the flax spinning and weaving

mill were at a charge of 6d each, and specimens of the beautiful

embroidery could be purchased.

Appendix (9). Jonathan James Harris died on May 28th 1915. He

retained the position of chairman and managing director to the

end of his life although for several years years failing health

prevented his attendance at the mills.

From an obituary in the Cockermouth Free Press dated 1915.

‘Elsewhere will be found the simple tale of the more prominent facts of Mr Harris’s life and works. Here it must suffice to pay tribute, sincere if brief to his personal worth. His was the quiet manner, reserved style and brevity in speech that are so often found in association with the truest kindness of heart and the most abundant generosity of disposition.’

It is at this point that I came to halt in my research of the

Derwent Mill. There is a fifteen year gap in the solicitors documents

that could provide any clue to the dealings of the company, and

only then in 1934 were there documents relating to the sale of

the Harris mills. After searching though old copies of ‘The

West Cumberland Times and Star,’ I finally found an article

relating to the appointment of a liquidator for the company but

no further mention beyond this. I shall therefore try and make

sense of what happened in these years and propose theories as

to why such a successful company and major employer of Cockermouth

should come to such a sad end.

After the death of Jonathan James Harris, the running of the firm

was taken over by his younger brother, Thomas Mason Harris, who

had to grapple with a declining business that had not been fortified

with capital during Jonathan Jame's control of the firm. This

was perhaps one reason for the decline of the Harris Mill.

‘The third generation makes the gentleman!. The pioneering captains of industry were obliged to devote their attention to their business in order to survive; but as they became established and their wealth accumulated, the second and third generation no longer strove to maximise profits but sought advancement for themselves in society, often by acquiring the trappings of gentility.’ (3)

In the case of Jonathan Harris and Sons, the pioneering captains of industry certainly continued into the second and third generations. Both Joseph and his successor Jonathan James Harris did much to develop the business with their constant investments in the latest technology, although they were both guilty of extracting funds that, perhaps, should have been set aside for helping the industry in harder times. It was Joseph Harris who first experimented with flax - discovering its use as a sewing thread and developing the lace manufacture and along with other members of the firm investing in the potential of flax being used as a substitute for silk. Jonathan James continued with these developments and certainly the sales and marketing of the products was achieved to the highest standards.

Thomas Mason Harris took over the firm in 1915, after the death of Jonathan James. The only account of the firm during the 1st World War was found very much by chance in an aeronautical book in the reference section of Workington library. ‘During 1919 an unusual machine was under construction at the Derwent Mills. During the war Jonathan Harris and Sons of Cockermouth had produced vast quantities of high - grade linen for the aircraft industry. The person responsible for the flying machine was 26 year old Thomas William Harris of Sunnyside, Papcastle who in addition to acquiring a war - surplus Renault aero engine, had also purchased a tank which he presented to Cockermouth.. Construction of the twin cockpit high wing monoplane was begun by the works engineering department under the direction of Robert Wild (later to found a garage business).’(4)

The linen was used in the construction of aeroplane wings and parachutes. The article then goes on to mention that the monoplane was modified into a sand plane and that during 1920/21 Will Harris was a familiar figure at Allonby, racing his machine at low tide on the flat sands between Dubmill Point and Saltpans. Will Harris was also a very active member of the Derwent Mills cricket team of which I have included a team photograph. Appendix (10).

The involvement of the Derwent Mills in the production of linen for the 1st World War led to many records of production being taken by the War Office. But even with this explanation I can find no trace of further developments after this period. The lifestyle of Will Harris does appear very much in keeping with the theory of third generation atrophy. Thomas William (Will) Harris died at Oxford on March 21st 1955 aged 72 years.

To put the blame for the closure of Derwent Mills totally onto

one person is perhaps unfair as there were certainly many other

circumstances affecting businesses at this time. The Derwent mills

exported large quantities of their goods overseas - to Sydney,

Melbourne, Calcutta and Paris. Another reason for their decline

could have been the growth of foreign competition and the collapse

of export markets. Textile industries in North Cumbria had declined

from the 1840s onwards. Jonathan Harris and Sons had managed to

survive, not only through its investments and new ideas but also

through its ability to export its unique products. With growing

self sufficiency from abroad and increasing trade restrictions

the export market was greatly affected.

‘From being Britain’s best customer, by 1938 India’s

domestic production of cotton goods had quadrupled and British

exports to India had fallen to one-tenth of the pre-war level.’

Textile industries had dominated international trade in cotton

goods providing 65 percent of the total world exports before 1914.

The war period had seen manpower shortages, reduced raw material

supplies and restrictions on trade.

Wartime conditions created a backlog of demand and with the world

depression which had set in, in 1921 not only was the export market

affected but home demand was also reduced. Although the product

exported by the Derwent mills had been unique, this aspect had

probably been relied on too heavily. There is no evidence of any

new investments in either equipment or ideas being made by Jonathan

Harris and Sons after the 1920s therefore faced with growing self

sufficiency from abroad and foreign competition they were soon

to lose their grip on the export market.

This lack of investment can also be an explanation in its own right for the decline of Jonathan Harris and Sons, thus giving support to the ‘early start hypothesis’. The first generations in the business were very involved in all major investments and ideas, from the installation of steam engines between 1835 and 1849, and 1852 the licence to use an invention for improving the manufacture of thread and yarn. Using the latest technology they perfected their lace making, sewing threads and eventually the Pure Flax Embroidery threads in the 1880s. With the ‘early start hypothesis’ it could be explained that with Jonathan Harris and Sons doing all the initial investment and development of new ideas, this then allowed late-comers to the industry to learn from his predecessors, use these ideas for their own benefit, using newer machinery and be more able to take shortcuts.

As I can find no evidence of any new investments then perhaps the tendency was to cling on to outdated machinery. This combined with complacency, would certainly allow for growth of competition from other areas contributing to the decline of the Derwent mills.Changes in women’s fashion in the 1920s could also have contributed to the closure of the Derwent mills. While most branches of the textile industry declined after the war, one branch, rayon (an artificial fibre made largely from wood pulp) expanded rapidly. Between the wars there was a shift towards lighter clothes for women.

‘There were no more corsets, to squeeze the flesh and make any exercise twice the effort it need be. There were no more skirts round one’s ankles’ to fetter walking and prevent running; no more swathing layers of under-clothes and no more elaborate hats. The slip replaced the petticoat and and she wore beach pyjamas on holiday.’ (5).

By the late 1920s a woman’s clothing might weigh no more than 1lb compared with 15-20 lbs of material in Victorian times. The new lighter clothing, also fabrics for upholstery etc. did not depend - with changing fashions- on the highly decorative embroidery used on the heavier fabrics 20 years earlier. Needlework itself - although still a popular pastime did not take the same prominence in schools or with the emancipated woman, as it had done in the past. Appendix (11). Although this theory perhaps played a part in the downfall of the Derwent mill, there is no way of knowing, to what degree it contributed to the decline.

With the closure of the Harris mill in 1934, there is one cause which cannot be ignored. The Wall Street Crash in New York in October 1929 caused world wide depression during the early 1930s. British exports declined by more than a third and unemployment rose to over 3 million. Tariff protection was brought in, in 1932 to relieve the situation, but recovery was slow and many British industries did not survive this period. Jonathan Harris and Sons was one of those industries and a small paragraph in the West Cumberland Times and Star dated June 9th 1934 depicts the closure of the once famous Derwent mills.

‘A meeting of the creditors of Jonathan Harris and Sons Ltd, who have carried on the business of manufacturing and making up of fancy goods, embroidery etc at Derwent Mill, Cockermouth for many years was held at Carlisle on Tuesday. Mr. H. C. Watson, accountant of Newcastle upon Tyne was appointed liquidator and he will negotiate in an effort to dispose of the business as a growing concern, failing which he will realise the efforts of the company otherwise. In the mean-time the services of a certain number of hands have been dispensed with but others are remaining to work off orders on the books. It is hoped that some enterprising firm will come along and carry on the business of this old established concern, who have become world famed for for their manufacture of Harris linen. Its passing will mean a severe blow to Cockermouth. Still there is more confidence in industry and without raising any false hopes, the outlook for the continuance of the business is much better to-day than it would have been if the decision to wind up had been made a year or two ago.’

The company did in fact sell to one Henry Campbell and Company Limited,of Belfast. Henry Campbell took over the linen thread side of the industry and the linen business was carried on by a new company under the title of Jonathan Harris and Sons (Cockermouth) Ltd., (1934). This ensured that a proportion of the mill premises continued to be used in the production of the famous Harris Linens. It also secured the employment of a certain amount of local labour. Jonathan Harris (In voluntary Liquidation)

Heads of Terms for Tenancy Agreement of part of Derwent Mills.

1. Premises Dying Shed and Finishing Room and Machinery and Plant

therein. Engine Room and Power Plant and machinery.

2. Rent At a rate of £600 for 12 months accruing from day

to day.

3. Terms 6 months terminable by the Landlord at any time by one

weeks notice. Bow Lane We agree to rent on behalf for one year from 29th September

1934 at a rent of £250 per annum. Sadly even under new ownership the mills did

not pull through.

A year later saw the final closure of the Harris Mill.

Although initially the essay ‘Derwent Mills, from prosperity to closure, a case of third generation atrophy’, sets out a case for the closure of the mill due to neglect, it is unfair, from the information I have managed to attain, to put all the blame on any one person. From humble beginnings the industry did prosper in the early days from enthusiastic, hardworking members of the family. Although they probably encountered many setbacks, in general the era was seen as a Victorian boom, in which Britain headed the technical innovation field - exporting and prospering. With the onset of foreign competition, the only way for the company to keep ahead would have to be from constant investment and development of fresh ideas. It appears as if the ‘Pure Flax Embroidery Threads’, were the final development and from there on the company continued to ride on this wave of success. With the material and fashion industry changing rapidly in the 20th century - combined with more leisure time which was perhaps spent on cinema visits, holidays etc, rather than sitting doing embroidery, - all this combined with the slump of the 1930s was too much for Jonathan Harris and Sons to contend with. After 100 years the Derwent mills finally closed. Appendix (12). But the history of Derwent Mills is not finished, for after serving as a flourishing shoe factory (Millers) a £2 million scheme has converted the Victorian edifice into modern flats.

Since publication the following details have emerged to correct

some of the interpretations of the study: Thomas Mason Harris's

son was Thomas William, known to the workforce as 'Mr Will'. Having

assisted his father for many years in the running of the mill

he became managing director upon his father's retirement . In

1934 he had the dreadful task of closing the mill. His son, Joseph

Angus, wrote; "My poor father had to make the decision to

close down voluntarily and look after the old workers who had

been with them for 25 years or more. They were bought annuities

because at that time there was no Beveridge Plan and the workhouse

would have been the alternative."

Bibliography: Adam R. A Woman’s Place 1910 - 1975.

Chatto & Windus 1975.

Bradbury B. A History of Cockermouth. Richard Bryers 1995.

Caine C. A History of Cleator. Reprinted Michael Moon.

Cockermouth Free Press. May 28th 1915.

Cannon P. An Aeronautical History of Cumbria, Dumfries & Galloway

Region 1915 - 1930. St Patrick’s Press, Penrith 1984.

Marshall J.D. & Walton J.K. The Lake Counties from 1830 to

mid Twentieth Century. Manchester University Press.

Mee A. The Children’s Encyclopedia. The Educational Book

Company.

May T. An Economic & Social History of Britain 1760 - 1970.

Longman1994.

Winkworth D.R. Printing and Publishing in Cockermouth. 1996. The

Royal Album of Arts and Industries of Great Britain. (Only one

page available).

Microsoft. Encarta 97 Encyclopedia 1993 - 1996 Microsoft Corporation.

Footnotes(1) The Royal Album of Arts and Industries of Great

Britain.(2) The Royal Album of Arts and Industries of Great Britain.(3)

May T. An Economical & Social History of Great Britain. 1760

- 1970.

Longman 1994. p.258 (4) Carran P. Aeronautical History of Cumbria,

Dumfries & Galloway

Region. 1915 - 1930. (5) Adam R. A Woman’s Place 1910 - 1975.

Chatto & Windus 1975. p.97